Welcome to Inkcap, a newsletter about nature, ecology and conservation in the UK, written and reported by me, Sophie Yeo.

This is your Wednesday feature. You can still read last Friday’s digest: River Bill & Glitter Litter.

Thank you to everyone who sent me ideas for using up my glut of apples! I think I’ve got enough recipes to get me through next year’s harvest, too. I’ll probably experiment this weekend.

Before it joined the EU’s predecessor in the 1970s, the UK was known as the “dirty man of Europe”.

This nickname arose in response to the nation’s filthy beaches, acid rain and belching power stations. European standards have forced a clean-up in the intervening decades, but, on nature, the UK is still lagging behind.

The dismal state of the UK’s habitats became apparent with the publication of an European Environment Agency report on Monday, assessing how Europe’s natural world has fared between 2013 and 2018.

Thanks to Brexit, this is the last time that the UK will be included in such a report, so I wanted to take this opportunity to explore the data.

The state of the UK’s habitats is glaringly bad.

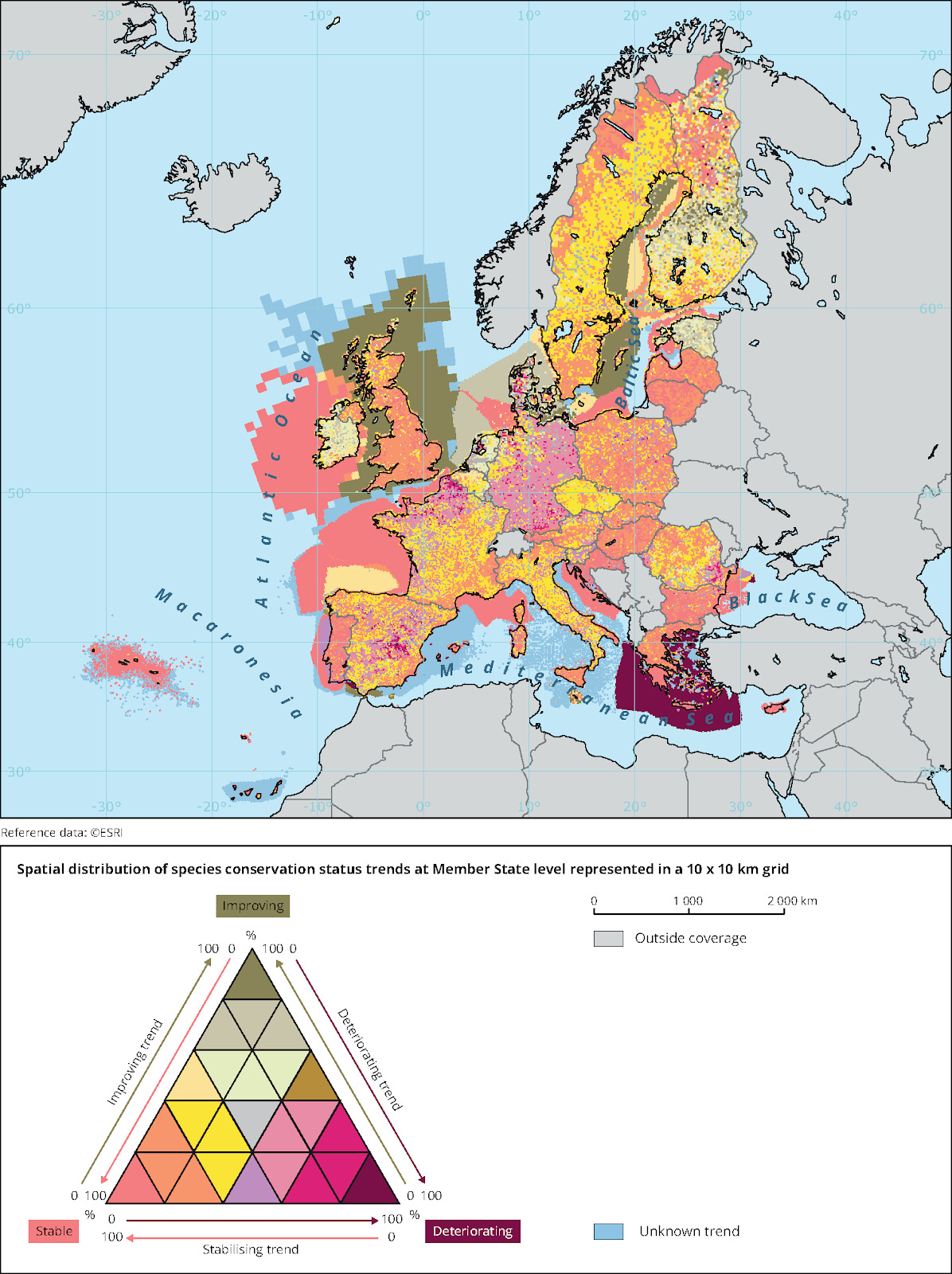

The map below shows the status of Europe’s habitats. The UK’s failure to protect its landscape is unignorable. The entire nation is painted solid red; the natural world is everywhere degraded.

(The triangular keys on the maps are really confusing. I feel like the authors need a lesson in data visualisation, but that’s another story. See the final section of this story for some thoughts on the data itself.)

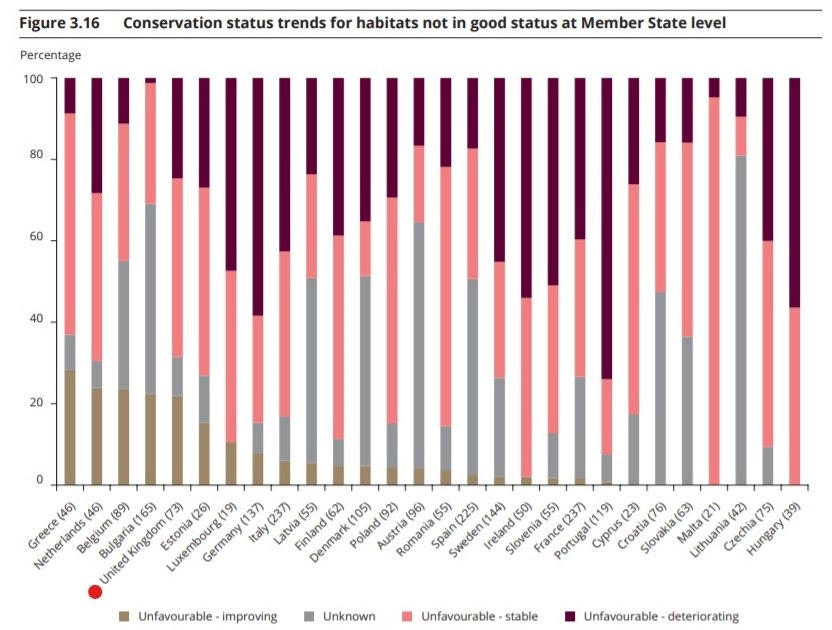

The graph below makes the UK’s position in this league table of destruction clearer (I’ve highlighted the UK with a red dot). There’s little consolation in the fact that Denmark and Belgium appear to have failed even more dramatically than the UK in safeguarding their natural environment; the three nations have the highest percentage of habitats in a bad condition.

Okay, but are the UK’s habitats improving?

The EU report looks at whether habitats are improving, deteriorating, or in a stable condition. The following data concerns habitats in poor or bad condition (of the habitats in good condition, 87 percent are stable and 12 percent are improving).

By this metric, the UK isn’t performing quite so awfully in comparison to its neighbours, as the map shows.

Again, the breakdown by member state makes it more apparent where the UK stands in relation to its European neighbours. Around 20 percent of the country’s degraded habitats are improving, which puts it among the top five states – although it’s important to remember that the UK’s landscapes were generally in a worse condition to begin with.

Putting that small victory aside, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that most UK habitats are either stable or deteriorating. In other words, the landscape is degraded, mostly it is not getting better, and in some cases it is getting worse.

So the UK’s habitats are in a bad way. What about species?

The EU report also shows the conservation status of species across member states, alongside an assessment of whether conditions are improving or deteriorating. The picture here isn’t quite so grim; but before we go into that, it’s worth considering this map showing the diversity of species across the continent.

This map shows that the diversity of plants and animals in the UK, and particularly in Scotland, is generally low compared to other European countries. Of course, diversity isn’t uniform, and some places are naturally richer in species – and the report doesn’t comment on the extent to which the UK’s diversity has decreased over the years. Still, it’s worth viewing the next graphs with this information in mind.

UK species are doing well. At least, they are not generally going extinct.

The following map shows how species as a whole are faring across Europe. It’s a more positive picture than the habitat maps, with the UK splashed green. Before getting too cheerful, though, it’s worth interrogating what it means for a species to have a good status.

The EU defines a species as being in a favourable condition if it can maintain itself within its natural habitat, its range is not currently being reduced and is unlikely to be reduced in the foreseeable future, and there is enough habitat to maintain its population on a long-term basis. In other words, it’s generally forward-looking, and doesn’t reflect large historic declines.

The report also says that, across Europe, widely distributed species are more likely to be in good condition. It’s possible that the UK’s success can be attributed to an abundance of common species that are doing well, while more sensitive species have already vanished, although the report does not explicitly comment on this.

This chart, broken down by member state, shows where the UK stands in comparison to its neighbours.

How is the UK remedying the situation?

As with habitats, the report looks at the trends for species over time across the continent. This map shows that species in the UK are generally in a stable condition – and that marine species are improving.

A warning about the data

I found this report interesting because it shows, for the last time, how the UK’s habitats and species are faring in comparison to the rest of the EU. It has clearly been a massive undertaking, and broadly reflects trends in nature across the continent.

That said, I want to sound a warning about this dataset and how it’s gathered – primarily because the data is self-reported, with the key parameters set by individual states. In addition, some nations have better records than others, and so will be able to paint a more complete picture of their natural world.

In particular, it’s worth noting that countries can choose their own baselines, known as “favourable reference values”, and this choice can influence whether a species or habitat is considered to be in a favourable condition.

Many countries, including the UK, chose 1994 as the baseline year against which they measure the state of nature, which is when the relevant EU directive came into force – but, obviously, Europe’s landscape was already much degraded by that point.

In other words, I’m taking it all with a pinch of salt.

Inkcap is 100% reader-funded.

If you value independent environmental journalism, please consider supporting Inkcap by becoming paid subscriber. (If it takes you to the landing page, simply re-enter your email.)

Got an opinion? Leave a comment, or get in touch by replying to this email.

Image credit: Romacdesigns

I don't think you understand what EU member states are reporting on. The UK reports on habitats and species of community interest in the Atlantic biogeographical region. Each of the biogeographical regions have different habitat and species lists corresponding to their climatic and edaphic conditions and the distributions of species across the Continent and so they are not directly comparable. Even then, not all countries within a biogeographical region have all the habitats and species of community interest, and thus the report masks big differences between countries, such as on the proportion of vegetation types protected that are dependant on agriculture, and of which the UK has many. We lack many primary habitats that other countries have. Moreover, we lack mammal species of community interest that most other member states have. Thus the UK is actually far worse than is shown.

Sophie this is very interesting but I take on board your last point about how difficult it is to interpret data gathered in different ways and over different time scales. However, I think it is important we don’t denigrate UK without good evidence because we need to take heart from the many success stories, including excellent rewilding experiments and reintroduction/ natural recolonisation/ expansion of many species, including a number of charismatic species like red kites, sea eagles, cranes, beaver, pine martin, etc The truth is the British Isle have never been as biodiverse as mainland Europe since the last ice age. The North Sea cut off the spread of species that may have eventually found their way here by land. The second important factor is that we are now more biodiverse than at any other time in the last 10,000 years. This is because many species have been introduced and become naturalised, and because climate change is encouraging some European species to head north. There have been relatively few extinctions and a large number of new species colonising UK, including species like brown hare, poppies and sweet chestnut which have become deeply rooted in our culture. Sometimes I think it would be worth celebrating these gains rather than, as the media is inclined to do, beat ourselves up as the ‘most nature deprived country in Europe’.